Civic Engagement

Discover what encompasses Civic engagement and the roles that libraries play in it.

Civic Engagement – Introduction

Focus

In this module, you will discover what encompasses “civic engagement” and the roles that libraries play in it.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will:

- Understand what civic engagement entails and how it has changed and evolved in the 21st century

- Discover and cultivate the role libraries play in civic engagement

- Identify the strengths and resources for civic engagement in your own community

Learning Tasks

- Read and watch the materials, taking notes on what challenges you, inspires you, or that you want to learn more about.

- Engage with the reflection questions. Some may be difficult and/or require accepting that you might not know or have thought about the topic. That’s ok!

- Complete the assigned activities to apply what you’re learning.

Materials You May Wish to Have

Pens and paper OR a word processing program.

Pre-module questions

- Where and how do you rate your personal level of civic engagement?

- How do you differentiate civics from politics, if you do?

- What are some of your local community vehicles for civic engagement?

What is Civic Engagement

We’ll begin this module by diving into what defines civic engagement. Have supplies to write both for the activities, as well as for responses to questions or thoughts that come up while engaging in the material.

Activity (Part I):

Create a bubble map with the words “civic engagement” in the center. What words, institutions, or activities do you associate with civic engagement?

Watch:

This 5 minute video “Unpacking Civic Engagement”

Read the following:

- How much does the average American know about Civics? Explore the results of the most recent annual survey of American Civics Knowledge conducted by the Annenberg Public Policy School at the University of Pennsylvania.

- The National Conference on Citizenship’s 2017 report on “Civic Deserts.” While reading, note your thoughts on the following:

- What are your thoughts on how they define civic engagement? Are there missing pieces or pieces that you did not consider?

- What has changed in civic engagement since the report’s release? How did the pandemic impact civic engagement since 2020?

- What role has social media played in community engagement–in other words, as people have connected online in ways they may have once connected in person in their own communities, what impact has that made on civic engagement?

- After completing the questions above, take a look at the Civic Health Index from 2021.

Activity (Part II):

- Revisit your bubble map. What words, institutions, or activities would you add to what you initially included?

Bonus listening:

- New Hampshire Public Radio’s “Civics 101” podcast pulls together both episodes that tackle common civics-related questions such as “what does separation of church and state mean?” with more contemporary and applied explorations of civics, including the

creation of the National Weather Service.

How Do Libraries and Civic Engagement Intersect?

What can libraries and library workers legally and ethically do to engage in or encourage civic engagement? Although not all libraries are democratic or public, even those which serve private parties are subject to policy and ethical considerations. Let’s turn to some of the sources of potential conflict and opportunity.

Consider the following questions:

- What are the ethical obligations for libraries as institutions to be spaces of civic engagement?

- What are the ethical obligations for library workers to be civically engaged?

- How and where does legislation–be it national or local–impact the library and library workers from being leaders in civic engagement? What non-legal beliefs or practices impact their civic engagement?

- Can libraries be neutral spaces if they are spaces of civic engagement?

Read the following

- Are Libraries Neutral? This ALA Midwinter roundtable is available to watch in full, though the highlights here are worth close attention.

- Read the professional Code of Ethics from the IFLA and the Code of Ethics from ALA and note your thoughts on the following:

- What tensions exist within each of these ethical codes individually?

- Where and how do these codes of ethics differ?

- In what ways are the ideas of neutrality addressed? Civic engagement?

- How is knowledge and practice of either of these ethical codes shared within the profession? It may be helpful to read about where and how library schools do or do not teach about ethics.

- Do these codes adequately define “neutral?”

- Is there a difference between a library being “neutral” with a library being “nonpartisan?”

- Book Riot and EveryLibrary Institute’s survey of parental perceptions of library workers, paying special attention to questions relating to civic and political engagement.

Activity

This activity is adaptable and can be as abbreviated or expansive as fits your needs. If you choose to do this within a shorter time frame, do not skip the reflection questions at the end.

Part i:

Depending on the type of library you are affiliated with, you will be subject to different policies, rules, or laws related to what you can do as an individual. For example, public librarians must follow not only the policies instituted by the library board but also those for public employees in the town where the library is located. School librarians may be in a similar situation, while academic or special librarians may find themselves beholden to policies at the institutional level (and for those librarians in publicly-funded institutions, there may be additional rules from the city, county, or state, too). Whatever the institution, though, all library roles are guided by professional ethics and guidelines, as well as policies and laws at the county, state, and federal levels. For some, there may also be guidelines or policies if part of a union.

Take a few moments to locate and review as many of the policies and laws related to you in your current position as possible. If you’re not currently employed, choose a previous library of employment or one in which you’d like to work.

Use the downloadable ecosystem template to note which rules, policies, or laws may directly impact your civic engagement capabilities as an individual. An example might be that you are not allowed to attend any public events wearing something which identifies you with a library facility beyond those coordinated specifically by the library, such as a designated storytime or farmer’s market appearance. You might have policies that state your car cannot have any political stickers or it might include specific dress codes which may bar apparel or accessories indicating any belief deemed political.

Rules in your community or county might govern whether or not you’re allowed to engage in protests or be part of any political organization. Laws may include rights to collective bargaining, the amount of time you’re given to vote on election days if your institution is not closed, and so forth.

These are meant to be examples–the purpose of this activity is to get a broad picture of how many different places your rights to civic engagement could be hindered, curtailed, or challenged. In some cases, your race, ethnicity, gender, disabilities, or other identities may put more restrictions on you.

You can adapt the template below however it makes sense to you; it’s meant to give a picture of the various systems and layers of decisions that impact you. The sample below does not include unions, for example, which may be placed closer to you than community policies but further away than workplace policies. The idea is to both understand your place within a series of systems and the rules which govern those systems.

Part ii:

You will complete the same activity again. This time, though, rather than looking for the policies, rules, and laws governing what you cannot do, create a map of where policies create space and encourage civic engagement. An example might be that your workplace opens late or closes early on Election Day or that outreach opportunities to other community organizations are not restricted.

Part iii:

Once your positives have been identified, reflect upon the following:

- Are there tensions between the two maps?

- Are there policies or laws you discovered which contradict one another, either within or across system layers?

- What ethical questions or concerns came up as you looked through the various policies, rules, and laws which govern your civic engagement capacities? Where or how might you choose ethical beliefs over policy or law?

- Did you discover anything that might be outdated or discriminatory? Where and how might you practice civic engagement with what you have unraveled in this exercise?

- Can you differentiate your personal life from your professional life?

Libraries As Spaces of Civic Engagement

Now with a bit of background and insight into what civic engagement entails–as well as having a sense of what it looks like in our contemporary cultural climate–let’s consider where and how libraries can make a difference by encouraging and cultivating it.

Watch:

Shamichael Hallman’s 15-minute TEDx video from February 2020, “Reimagining the Public Library to Reconnect the Community.”

Consider the following:

- What civic engagement resources does your library offer? These could be spaces available for community use, election-related candidate forums, voter registration, or anything else under the umbrella.

- What civic engagement programs have you seen at other libraries which have excited or inspired you?

- In Hallman’s talk, he brings up the idea of consuming vs. contributing to civic engagement. Where and how do you see these two activities play out in your public library? In your ideal space, how would you find a balance between the two? What might that require?

- Hallman talks about a beautiful vision of community members of different backgrounds, races, religions, and sexualities embracing one another in the library. Given how politicized libraries have become in the public sphere since his pre-COVID talk, particularly around these very issues as they are presented in the books and programs offered by the library, is this possible? What might be required to make his vision a reality today?

Read:

- Libraries Transforming Communities: The Movement Toward Civic Hubs by Kevin Hummel in the National Civic Review:

- Leadership Brief: Libraries Leading Civic Engagement from the Urban Libraries Council

- Browse ALA’s resources on Civic and Community Engagement IV. Pulling it Together

Pulling it Together

With the knowledge and insight gained here, alongside your own experience and prior work, here’s an activity that will pull all of those pieces together and become a resource for civic engagement for you and your institution.

Asset Mapping Activity

First, watch this short video overview of asset mapping.

Asset mapping is a way to identify and describe the strengths in a community. While it can be common for the library to look at service holes in the community, this process looks at what is going well in the community and encourages getting to know parts of a community which may be overlooked. Asset mapping can be a lengthy process, involving a wide variety of research methods. The purpose of this module activity is to practice thinking about and researching the strengths within your community, so it will not be complete nor comprehensive. If you are taking this module with a group, feel free to work on this together. You can complete this with pen and paper or with digital tools of choice.

There is not a single “correct” way to asset map. But three general buckets of information can be helpful in researching and connecting to the strengths in your community. These include individuals, institutions, and citizen associations.

Scenario

Local elections are happening this year and you want to build a resource hub for the library. Develop an asset map that includes the following three categories:

- What individuals within your community might be an asset in helping you create this resource? What qualities do they possess?

- What institutions within your community might be an asset in this project? What qualities do they possess?

- What citizen associations are within the community who might be an asset in this project? What qualities do they possess?

Reflect

Take some time to respond to the following questions about this exercise:

- What category of asset mapping was most difficult? Easiest?

- What assets were you surprised to find an abundance of in your community?

- Were there any assets you initially considered then elected not to include? Why?

- How did you find the information you needed? Where and how did you record your research pathways?

- Where does asset mapping tie into civic engagement?

Bonus

You can take this activity as far as you might like. A list is going to be valuable, but you could also create a map of these resources in your community (being mindful, of course, of individual privacy). Where are all of your institutional assets located within your community? Are there trends? What about your citizen associations: where are they holding meetings?

Post-module Reflection

- Did your thoughts from the premodule questions shift as you moved through the readings, videos, and activities?

- What is one big thing you will take away from this lesson and implement into your work? What is one thing you are eager to share with a friend or colleague?

Community Organizing and Activisim – Introduction

Focus

In this module, you will learn about community organizing and activism and how they tie into the work done in libraries every day.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will:

- Consider the roles of community organizing, advocacy, and activism both within and beyond the walls of the library.

- Understand the role you play in activism and advocacy, including where and how your activities might be limited by your work position.

- Identify the importance of self-care and brainstorm your own plan for self-care.

Learning Tasks

- Read and watch the materials, taking notes on what challenges you, inspires you, or that you want to learn more about.

- Engage with the reflection questions. Some may be difficult and/or require accepting that you might not know or have thought about the topic. That’s ok!

- Complete the assigned activities to apply what you’re learning. Some activities will require returning to those completed in Module 1 of this section. All of the activities are meant to apply the lessons while also being applicable to your life both within and beyond the library.

Materials You Will Need:

- Pen and paper or word processing tools

- Your responses to the policy ecosystem and community asset mapping activities in Section 4, Module 1

Pre Module Questions:

- How do you define community organizing? Activism? Advocacy?

- Who in your community is engaged in organizing? Who do you point to as activists in your community?

- Consider the above questions in relation to the Community Asset Map you developed in Second 4, Module 1: where are there overlaps? Who or what groups might be missing from your asset map that you’ve identified here?

Defining Community Organizing and Activisim

What, exactly, is community organizing? What defines “activism?” Dive into these questions and more below.

Activity:

Take Omkari Williams’s Activism Archetype Quiz–you will need to enter your email address–to discover what type of activist most aligns with your personality type.

Watch:

The 15 minute TEDx Talk “Community Organizing Say What?” by Ray Friedlander:

Read:

- Deepa Iyer developed a Social Change Map that outlines several roles that people take in community organizing and activism. Read about the framework here, the updating of the framework here, and about how the framework is a useful tool for social change. Consider where and how the framework evolved over the course of Iyer’s engagement with and understanding of activism. Note: Iyer created a workbook available for purchase and use with organizations to use. The links included here are permitted for use and the visual for sharing with attribution.

- “Organizing Together: The Library As Community Organizer” by Melissa Canham-Clyne in the Urban Library Journal.

- “Get Organized” by Terra Dankowski for American Libraries.

- “Community Organizing and Activism: Hampshire High School,” a slideshow case study of putting the work into action.

Reflection:

- You’ve looked at two different tools to categorize the roles that change makers and activists take via the quiz and the social change map. Did one resonate with you more than the other? In considering each, what strengths did you see that you bring to the table in making change? Do either of these change whatever beliefs you may have about your own role in activism and/or community organizing?

- In the short writeup about the “Get Organized” panel at the 2023 LibLearnX conference, every speaker talked about an issue that catalyzed them into action. What issues within the library have catalyzed you? In what ways did you respond? If you have not yet had this experience, what issues can you see now or imagine in the future as catalyzing?

- Returning to the policy ecosystem created in Section 4, Module 1, consider the following:

- Are there policies which restrict your ability to personally engage in activism as a private citizen? What about as an employee of your library or community?

- Are there policies which hinder the ability to engage in community organizing in your library as a private citizen? What about as an employee of your library or community?

Activity:

Return to your community asset map (Section 4, Module 1) and think about the readings in this module, particularly the piece by Canham-Clyne and the slideshow about Hampshire High School and its performance of The Prom. What resources in your community has your organization developed good relationships with and used to consider programming, collections, or other library services? What groups have you not tapped? As you think about these questions, consider the following:

- How does the library begin to engage with community groups when there is no prior relationship? Select one group and consider how the library might engage with them in a way that is mutually beneficial. Write a plan for how they might be approached, who in the library might be a great person to do the outreach (don’t overlook the entire staff and the strengths they have as leaders), and consider what value such a partnership would have for both your organization and theirs. What does a good partnership look like?

- In reviewing the asset map, do you recognize any populations, groups, or interests which may have been missed in its initial creation? You may not be able to immediately name what those groups are–they’re missing for a reason–but list the community organizations, organizers, activists, and special interests which may be missing. Who within your library might know about these organizations?

- Consider now the inverse: how and where can you be a resource or advocate for needs being expressed within any of your identified community groups and get the word out to those groups?

Bonus Resources: Lauren Comito, a Brooklyn Public Library branch supervisor and one of the founders of Urban Librarians Unite, gave a talk for the Wild Wisconsin Winter Web Conference about community organizing in libraries. It’s a 45 minute talk and worth it for further context and idea generation.

Deepa Iyer is the creator of the Social Change ecosystem [see above]. She and her team put together a series of videos about the framework worth diving into. Each is an hour long, so this is a time investment, but it’s well worthwhile whether you do it with her workbook or without.

Identifying and Engaging Library Advocates

How can you figure out who your library advocates are and help catalyze them into activists for your library?

Activity:

Set a timer for 5 minutes and brainstorm everyone you’d consider a library power user and/or advocate. This might be a regular storytime family or a local politician or an individual who is engaged in the Friends of the library. Your community asset map can be useful here.

After you complete your brainstorm, consider the following:

- Who are the advocates you can name in your library? What similarities or differences do they have from one another? Are there any groups of people or types of library users you might have overlooked (for example, if you are a children’s librarian, did you overlook seniors who regularly attend adult programming in the evening or maybe you overlooked members of your community’s Latinx population)?

- In what ways can you turn your power users/advocates into activists?

Read:

Note that much of the literature around library advocacy focuses on budgetary issues. Pearson’s short white paper differentiates the financial side of advocacy from other challenges libraries need advocates from. Budget advocacy is vital, of course, but it is worth questioning why the literature is less robust when it comes to identifying, developing, and deploying other advocacy work on behalf of the library by those not employed by the library.

- “Sustaining Local Library Advocacy in Today’s Political Environment” by Peter Pearson in The Political Librarian

- “Turn Library Advocates into Activists” by PC Sweeney

- “The Library Advocacy Gap: Increasing Librarians’ Political Self-Efficacy” by Sonya Durney

- “Critical Optimism: Reimagining Rural Communities Through Libraries” by Margo Gustina

- ALA’s Frontline Advocacy Toolkit

- Look at how one public library encourages their patrons to engage with the local media on their behalf.

Activity:

Utilizing your community asset map and your policy ecosystem (Section 4, Module 1), work through the following scenario.

Scenario

Your library or school board has seen significant turnover in the most recent election. Four of the seven members are new, and they ran on a slate together that emphasized parental rights and more oversight of the library/media center. The slate received significant funding from both a local political party, as well as political groups outside of your state.

At the latest board meeting, one of the new members suggested that it was time to update some of the collection development policies in the library. They are suggesting two things: first, that children under 18 get a signed permission form by their parent or guardian before they access any print or digital materials (an “opt-in” form) and second, that all of the books in the library be given a rating. This board member presents a sample of what the rating system might look like.

A majority of the board is interested in talking more about the possibility, including those who have served on the board for several years.

What do you do?

First answer the following:

- What is your initial response to this situation? Explore the physical, mental, and emotional experience of what comes up for you. (We will revisit this in Part III below).

- Looking at your policy ecosystem, determine what you, as a library worker, can and cannot do in this situation. Are there any limitations? If so, in what ways do you choose to employ your personal ethics to engage with the scenario?

Engage the community

- Who within your community should be the first to know about this policy consideration?

- What methods would you use to inform your community about the potential policy change?

- Considering your style of leadership in community organizing, how would you ensure that community stakeholders knew what was happening?

- What resources or tools outside of the immediate community might be helpful or applicable in this situation? How can you utilize them?

Map it out

Taking all of the considerations above, develop a plan–you can make it any way you’d like, whether as a step-by-step list, a visual map, etc.–for how this scenario could be addressed before the next board meeting. Who will do what and in what order? You can assume buy-in along the way (for example, if you ask a librarian in another state to show you their collection management policy that addresses some of these concerns, they agree and send it to you).

Reflect

- What role did you put yourself in while considering how you’d address this situation? Did it feel natural? If so, what personal strengths made it feel that way? If not, would you reconsider your role or do you see potential places to strengthen particular skill sets?

- Did your community have everything it needed to address the situation?

- If the outcome of the scenario was not what you hoped, how would you and the people you worked with address that? What resources might you find useful for handling defeat without feeling defeated?

- What was the most difficult part of this activity? What was most rewarding or beneficial?

Self-Care

To have a successful career, you need to practice self-care. This becomes even more evident when engaging in the work of activism and community organizing, either on the front lines or in the background. Too often, we write off self-care–who has time?–or we consider the methods of self-care–such as a nice bubble bath–to be meaningless or silly. The reality is we all need self-care and we define it in the ways we need to recharge.

One person’s self-care might be a daily run; for others, it might be that nice bath; still for others, self-care might be taking pottery classes or making the effort to cook dinner every evening or gardening or journaling or seeing a therapist. Self-care is just that: the care you do for yourself to refill your cup. If one thing does not work for you, try something else. If you don’t feel like your cup is filled by a gratitude journal or meditation, that’s okay!

Read:

- Trauma in the Library: A Resource Guide

- “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves” by Fobazi Ettarh

- “The Weight We Carry” by Rebecca Tolley. Of particular note is the distinction between micro and macro self-care.

- Explore the 8 dimensions of wellness in Debbie L. Stoewen’s “Dimensions of Wellness: Change Your Habits, Change Your Life.”

- Try the “You Feel Like Shit-A Self-Care Game.” Not all of the prompts will be applicable, but this is a super approachable, user-friendly guide to ground you when you’re in the midst of fight-flight-freeze or other mental health challenge and need to find grounding.

Activity:

These two activities, as with all of the activities in these modules, are meant to be useful resources in your everyday work life. Keep these somewhere accessible. That might mean a physical copy at your work desk or a digital copy you can access quickly on whatever device you like to use. Feel free to be creative!

Create a Safety Plan

When you find yourself experiencing a mental health challenge, be it one that you have experience navigating or one which might be deemed a crisis, do you know how to keep yourself safe? A safety plan will help you do just that. Before you think that keeping yourself safe is obvious or basic, recall that the fight-flight-freeze response moves us out of our most rational thinking brains. We may forget or overlook the most “basic” actions we can take.

Safety plans are evidence-based tools used in therapy with suicidal clients, though their utility extends beyond those with the most mental health needs.

Your safety plan can take any shape, but it should include the following information:

- Situations or scenarios which you know can trigger strong mental, emotional, or physical responses. These are your triggers.

- Identification of safe environments and/or how you can make an environment you’re in safer. For example, if you experience a mental health challenge while working a public service desk, what can you do to make that as safe for you as possible? It is appropriate to note you might need to leave that space.

- Strategies that help you cope when you feel overwhelmed. Include here the things you can do on your own, as well as those in which you can engage with others. These ideas can be split into multiple categories, differentiating between strategies you can use to distract yourself and those which help you cope with a situation.

- People who you can reach out to when you need help–friends, family, coworkers, other people in your social networks–alongside their contact information.

- Health or wellness professionals you use and their contact information.

Map Your Core Values

A core values map can be helpful for when you’re feeling overwhelmed. It is meant to be a reminder of your priorities and your passions and can be helpful in creating self-care routines–and it can help you feel less pressure to engage in self-care that doesn’t feel like it works for you.

This activity is a modification of one created by Andrea Scher of Superhero Life and it has two parts. Consider doing this one analog, since there is some value in writing this down. You can always recreate it in a digital version.

Part I.

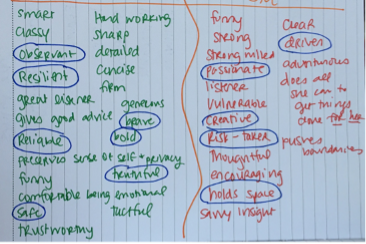

- Grab a sheet of paper and fold it in half.

- On one half of the paper, write down the name of someone you admire. It can be anyone, whether you know them or not. Beneath their name, list some of the things you admire about them.

- Repeat #2 but using the name of someone else you admire.

- Now look at both of your lists and circle the words that jump out at you. Don’t think too hard. Trust your instincts. If it feels like you may have missed some qualities you admire in one or both of your people, go ahead and add them.

- Which of the words that you circled resonated most? Choose anywhere between 2 and 5 and write them down. If any of the words or ideas can be combined into a different word, you’re welcome to choose the new word.

What you have might look something like this:

Part II

Because this part requires a little more writing, if it is easier to use a word processing tool, go for it.

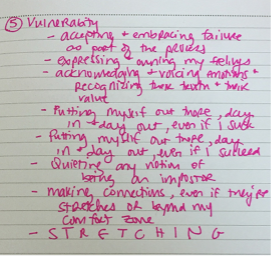

- For each of the 2-5 values you listed, ask yourself what that value means to you. How does it show up in your life? What ways do you connect with it? You might not have any examples and that is okay. Values can be aspirational! What matters is that these values make you feel something. If more ideas for values come to mind as you’re doing this, that is okay!

What you have might look like this:

- At this point, you have found some of the values you circled or listed really connect while others do not. Perhaps your list of 5 winnowed down to a list of 3 or you experience the reverse, and your list of 3 bloomed to 5.

Congrats: you’ve just discovered some of your core values. There are a lot of things you can do with this, and the easiest might be to write each of those words down in an easy-to-see place. They can help ground you during tough times, and they can help motivate you when you’re feeling stuck.

Mapping Core Values

You can take this activity as far as you’d like. You have listed your connections to each of these values, but perhaps now, you create a bubble map with each value in the center with how you can apply them in your work coming outward. You could do this activity with a group of library workers and see how your bubble maps connect or overlap–if you value vulnerability and a colleague lists empathy as a value, where and how can your values connect to strengthen each other?

This same value mapping can be expanded with community partners–perhaps it’s a program opportunity with some of the groups you’ve identified in your asset map.

Post-Module Reflection

- Did your thoughts from the premodule questions shift as you moved through the readings, videos, and activities?

- What is one big thing you will take away from this lesson and implement into your work? What is one thing you are eager to share with a friend or colleague?

Public Speaking – Introduction

Focus

In this module, you will learn about the power of public speaking and how you can strengthen your own skills.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will:

- View several talks addressing public speaking, each of which offers valuable insights for understanding why it is often a scary prospect.

- Consider the different ways you already engage in public speaking.

- Evaluate your public speaking strengths and weaknesses and identify the types of activities you might try to build your skills.

Learning Tasks

- Read and watch the materials, taking notes on what challenges you, inspires you, or that you want to learn more about.

- Engage with the reflection questions. Some may be difficult and/or require accepting that you might not know or have thought about the topic. That’s ok!

- Complete the assigned activities to apply what you’re learning.

Materials You Will Need

- Pen and paper or a word processing tool

Premodule questions

- What is public speaking?

- What makes for a good public speaker? What qualities do they possess?

- Are there things that you have seen or heard public speakers do that you don’t like? What bothers you about it?

- What emotions do you have around the idea of public speaking?

As you begin this module, you might be thinking that you don’t engage in public speaking and/or that you never will. The fact is you probably do a lot of public speaking. It just might not be formal. Consider your experiences speaking in front of groups of people, be it during a book club, storytime, presentation to a local community organization, or elsewhere as you move through this section.

Activity – Part 1

We will use this activity again at the end of the module, so take some time with it to begin. Fold a piece of paper into 4 parts (or create 4 boxes on a word processing document). n the first box, spend some time writing down what you think your strengths are when it comes to speaking to other people. Don’t limit yourself here. Write as many strengths as you can!”

Once you’ve completed that, move on to the second box. This is where you’re going to write down any fears, weaknesses, or challenges you have when it comes to speaking to other people. This time, do consider this to be “public” speaking in that you’ll be talking to or in front of several people at one time. Don’t belabor this one. Pick 3-5 at most to write down.

Set this aside but feel free to add to it as you move through the rest of the module.

Watch

- This short video from Ze Frank offers a how-to on public speaking. After you watch, consider what you agree with and what you disagree with. One of the most interesting things about public speaking is that everyone has a different opinion on what works and what does not.

Public speaking is more effective to see than it is to read about. Each of these videos are from various TEDx talks, which have a distinct style to them. Not all public speaking happens in this style, of course, but watching several of these not only offers valuable insight and applicable tips for your own public speaking but also showcases how each person brings their own manner of presenting.

- The 15 minute TED talk “Why Do We Fear Public Speaking” from Dave Guin (note: there are some audio hiccups in this video). After you watch through for the content, pause to think about how Guin gave his presentation. What did you notice about his body language? His use of filler words (such as “um” or “uh”)? What was he doing with his hands? Did his body or face convey any expression of feeling? What stood out to you as strengths in his talk? What about any weaknesses? What did you like and dislike?

- The 10 minute TED talk “Why We Fear Public Speaking” by Taylor Williams. Watch for the content. Pay special attention to how Williams defines public speaking and think about where or how that applies to your work in the library. Then, when you finish, take the time to answer the questions you’ve answered above about how Wlliams presented, what you liked and disliked, etc.

- The 18 minute TED talk “How to Trust Your Voice and Speak With Confidence Anywhere” by Mariama Whyte. Watch for the content and consider her three-part framework for trusting yourself when you speak. Then, when you finish, take the time to answer the questions you answered above about how Whyte presented.

- Finally, watch the 16 minute TED talk “Why Do We Fear Speaking On Stage?” by Pratik Uppal. Watch for the content, and pay attention to the demonstration he gives. When you finish, take the time to answer the questions you’ve answered above about how Uppal presented, what you liked and disliked, etc.

Reflect

- Which speaker was your favorite? Why?

- Which speaker was your least favorite? Why?

- Was it the content or the delivery of the speeches that impacted your preferences? Did you consider yourself the intended audience of any of these talks more than another? If so, what made the difference?

Read

- “Boost Your Public Speaking Skills” by Ann Ford for American Libraries.

- WebJunction has an excellent handout on the common challenges of public speaking and tips and tricks to address them.

- Are filler words like “um, hmm, uh” bad? Here’s what the research says and why discourse about these parts of speech might be gendered and ageist.

- “How To Recover from Public Speaking Mistakes” by Linda Ugelow

Consider

One theme that comes up in the readings is that people are not interested in presentations where the speaker reads off a slide deck. With the increased use of Zoom for web speaking and better knowledge of accessibility, neurodiversity, and learning styles, do you think this has changed at all? Are people more accepting of bulkier slide shows and reliance on them by speakers?

Activity – Part 2

Return to your list from the activity earlier in the module. Now we’re going to fill in the remaining boxes. In the next open box, take some time to think about what you’ve engaged with in this module. Write down how you can use the strengths you identified in the first box to help you push against or overcome the challenges you identified in the second box. Don’t just list it, though; draft how you would implement the strength. For example, if you listed humor as a strength, perhaps that humor can be parlayed as a way to overcome nerves you might have around being in front of other people. You might begin whatever you’re talking about with a joke about how nervous you are to cut the tension or you might think about how, if you make a mistake in your talk, you can reference a mistake made by someone in pop culture as a means of reminding yourself you’re human and that other people know mistakes happen.

Set your paper aside and grab a fresh sheet. Now we’re onto putting this into action with the following scenario.

It’s the morning of a library board meeting, but your boss who usually attends is out sick and asks you to attend. You’re asked to step in to talk with the board and meeting attendees about the upcoming summer reading program being put on by the library. Consider this scenario in three parts:

- What would you do to prepare?

- You arrive at the board meeting and discover that there will be not just the board and a few community members in attendance, but your city’s mayor is there, alongside several other high-profile people. Imagine yourself at the front of the room now and write down the steps you would take to feel confident and competent? If you would already feel that way, what is one thing you could do in that moment to make your talk sparkle just a little bit more?

- How would you assess how you did in the hours and days afterward? In other words, what kind of self-assessment or reflection would you do? What would you tell your boss when they ask how it went?

- Where did you pull from your strengths to feel more confident?

In this scenario you have no pressing obligations in the library–i.e., no time at the reference desk or programming to do–so you do not need to worry about those. You also do not need to worry about coordinating things like technology if you choose to create a slideshow or other visual. Focus solely on the speaking portion. You have all of the information and materials you need.

Move into the final box on your first paper. Thinking about this scenario, the videos you watched, and the readings you explored, make a list of things you think would be valuable for you to try to strengthen your public speaking skills. Don’t just list what you learned; list what you want to practice.

Post-Module Reflection

- Did your thoughts from the premodule questions shift as you moved through the readings, videos, and activities?

- What is one big thing you will take away from this lesson and implement into your work? What is one thing you are eager to share with a friend or colleague?

Introduction – Editorials and Media Campaigns

Focus

In this module, you will learn how to understand the current media landscape and where and how it impacts the library.

Learning Objectives

At the end of this module, you will:

- Understand the decline of local news and rise of hyperlocal media/social media

- Consider how the library can work with local media

- Recognize the ways the Freedom of Information Act applies to you in your workplace.

Learning Tasks

- Read and watch the materials, taking notes on what challenges you, inspires you, or that you want to learn more about.

- Engage with the reflection questions. Some may be difficult and/or require accepting that you might not know or have thought about the topic. That’s ok!

- Complete the assigned activities to apply what you’re learning.

Materials You May Wish To Have

- Pens and paper OR a word processing program.

Pre-module Questions

- What are some of the local media outlets in your region? Do you have any connection or contacts with those outlets?

- Where is the library accessible to users beyond its physical presence or its website?

- What do you know about the Freedom of Information Act and how it impacts the work you do in the library?

Editorials and Media Campaigns

Librarians need to be strong communicators. This extends to public speaking (see Module 3, Section 4) and to ensuring communication about the library via the media is crisp, clear, and effective. Not only is this important for marketing and publicity–you want patrons to know the who, what, where, when, and why of every event–but it’s important for further cementing your library’s vital role in the community.

One of the biggest challenges in our ongoing media landscape, though, is that local news has been disappearing. Outlets that used to have a regular library column have consolidated with bigger papers and now cover a larger area or have shuttered completely. This has led to a rise in information going unshared in trusted outlets, as well as a rise in information being passed around on social media. There are benefits and limitations to this, of course. Where once the library had the authority in a newspaper to share what was going on, now anyone can post about what may or may not be happening in the facility, whether it is verifiable or rumor.

Read

- Northwestern University’s Medill Journalism School’s Local News Initiative is a powerful resource on the changing state of local media. There is a lot to dig into here, so take some time to poke around and learn about how much journalism has changed since the early 2000s. Pay particular attention to the annual “The State of Local News” Project and see where your community stacks up.

- PEW Research’s report on how civic engagement is lost as newspapers are lost (see Module 1, Section 4, for where and how libraries can be key in cultivating civic engagement).

- “Libraries and Local News: Expanding Journalism, Another User Service Grounded in Reference” by Chris LaBeau for the Reference and User Services Association

For libraries, the rise of hyperlocal social media can be leveraged to create a voice for the institution and to be the authority on that institution. But don’t overlook the media that does still exist. Even if many newspapers have disappeared or been consolidated, you might have one you can regularly connect with.

Where are some of the other places where you can share what is happening in the library and be the authority on your own institution?

- Refer to your asset map from Module 1, Section 4. Do any of these assets have publications you might be able to submit a story to? As you develop relationships with these groups, don’t be scared to ask if they know of newsletters or other outlets run by members or friends of members who might be interested in hearing from the library. Librarians can do good research, but not all information is readily findable. “Smaller” outlets might hit a specific audience or demographic that isn’t as easy to Google.

- How journalists have used social media outlets like NextDoor–is this viable with the library? Can the library tap into community Facebook groups outside of their own page?

- “When Local Newspapers Close, What Can Libraries Do?” by Rebecca Hill for the Office for Intellectual Freedom at ALA proposes the ways libraries can fill the gap left by closure of local media. Within this are some great ideas for how to figure out what the sources of information are in your own community.

Whether you have a robust local media landscape or your biggest information resource is the local community Facebook page, it is vital to know how to effectively communicate with the media. Like you were probably taught in elementary school, journalists tell compelling stories using the 5Ws: Who, What, Where, When, and Why. Many also consider the H, or How. Use this as your own framework for writing, too–it’s a simple method but it’s effective. Structure whatever you’re writing to hit those six items as soon as possible, within the first sentence or, at latest, by the end of the first paragraph. And of course, don’t forget to have some style or inject your voice/the institution’s voice into the work.

- ALA offers a basic structure for writing a letter to the editor on behalf of your institution. This structure works for any topic–not just budgetary issues!

- NPR’s training materials include a handy guide to writing short and a very helpful accuracy checklist.

Media is two way, of course. This means that as much as you might benefit from tapping the media, the media may reach out to the library as well. The intention may be for a story that shows the library in a good light, but in some cases, it might be to uncover whether or not a story shared on social media is true or not. So what happens when you are at the receiving end of a media inquiry? What do you do if the media–or even a regular citizen with no known media ties–submits a Freedom of Information Act request for information?

- Start with reading the National Security Archive’s FOIA basics to understand the law. Browse the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), then find your state’s FOIA or similarly-named law and become familiar with what information can be requested if you work for a public institution.

- Some of the uses the average person might have when it comes to FOIA.

- Libraries uphold the privacy rights of users, but what about staff members? Read #6 on ALA’s Privacy and Confidentiality Q&A.

- When it comes to communicating with the media outside of FOIA or materials requests, become familiar with three key phrases you are entitled to ask for: on the record, on background, or off the record. If the media does not grant you what you ask for, you’re not under obligation to speak; if they want that information, they can find it through other sources or means.

- Take the time to find out who your FOIA officer is. It might be someone on the library staff, someone in administration at your school, or an individual working at city hall. They will be your best source of information about local laws governing your rights and privacy, and they will be your point of contact for any FOIA requests the library might receive (or which you might receive).

If you work in a public institution, know that work you do on any work equipment–physical or digital–may be subject to FOIA. The intricacies of the law may exclude some types of communication from being shared with a requester, and in absence of FOIA expertise, play it safe by assuming anything may be asked by anyone at any time. Consider what work you do via your library email vs the work you might do via a personal email outside of the library. Consider, too, your personal social media. It might not be FOIA-worthy, since it is done on your own time and belongs to you, but any connection it might led between you and your library could be used by journalists or citizens in whatever story they’re working on.

- Read “‘So Excited’: Emails Show Librarians Plotting Drag Shows” in the right-wing outlet The Federalist. This is an example of how normal use of work email at the library can be misconstrued–and damage the library and its staff. The employees here are not at fault but this story serves as a reminder of how outlets might choose to use material they acquire.

In general, if you wouldn’t want it on a billboard without context, don’t put it in writing or email subject to FOIA.

- Pursue Violet Blue’s personal privacy checklist and utilize any of the suggestions which might help you protect yourself on your personal time.

Sample Communication

- ALA’s sample letter for public advocacy

- The National Freedom of Information Coalition has several sample FOIA letter examples.

- This editorial from Daily Progress is an excellent example of the local paper advocating for intellectual freedom in the local school district. For an example of a library advocate using the local media to advocate for their library, scroll down to the second letter for Sunday, July 2, 2023, in The Sentinel Record. Both of these letters are useful reference points for writing your own letters to the editor, as well as examples of harnessing the power of your community to do that support on your behalf (See Section 4, Module 1 and 2).

Note: Communication between school librarians and the media is often mediated by the district itself, and because of this, both of the activities in this section are public library based. For those in such positions, either consider a parallel situation applicable to you OR put yourself in the position of a public librarian.

Gender Queer: A Memoir

Local elections are coming up, and you want to make sure that people in your district not only vote, but that they know there are several library-related issues on the ballot. Among them are three trustee positions, as well as a small tax/millage increase. You have two local newspapers, as well as a paper that covers a larger region in your area. Draft the following:

- An email to the newspaper staff asking if they would allow the library space to write a story about the initiatives on the ballot OR if someone from their staff would be interested in covering the story.

- A letter to the editor to be published as-is in their publication. The word limit for letters to the editor is 300.

Activity:

Read the following scenario, then complete the exercise. There are no right and wrong answers, and you might not be able to complete everything without the input or help of others. That is okay–write down who you may need to talk with and how you would use their expertise or experience to navigate the situation.

Scenario

On a Friday afternoon in your local community Facebook after the library had closed for the day, someone posted that the library had recently put up a display of “pornography.” The images included on the post were from a Pride display in the children’s area that was constructed for June, and the poster included pages from Gender Queer and an LGBTQ+ positive puberty book. Because the post went up at a time most people were not around on social media, it did not get a lot of attention. A couple of comments said this was gross or disgusting, and a couple of others said they did not believe this would happen in their library.

When you arrive in the office on Monday morning, there are several messages from the weekend staff about an angry phone call from a local parent about “inappropriate books” they saw on the library’s website. You also open your email to find a Freedom of Information Act Request (FOIA) that you’ve been copied on. It came from a reporter at a paper who covers news across several counties in your region, though they do not live in your library’s community nor county. The FOIA is asking for every email and document from the past year among all staff covering topics that include the terms LGBTQ+, puberty, sexuality, pornography, pronouns, they/them, trans, gender queer, transgender, and Pride month. The request also asks for receipts for every book purchased for the library in the same time frame, as well as your policies on book displays (this is not something you have in your collection development or programming policies available online–in fact, you don’t have one at all).

You walk by the Pride display and notice that it is nearly empty, after having been fully stocked on Friday. Gender Queer is among the titles not on display any longer, and you can’t help wondering if it was taken out by someone genuinely interested in reading it or by someone who plans to complain about the book.

Answer the following. Remember there is no right answer to any of these, and working through these questions might lead to more questions, too.

- What is your first instinct in how to handle this situation?

- Who needs to immediately know what happened? Consider not just your supervisors or those you oversee, but people in the community, too.

- Where or how do you respond to the initial Facebook post? What are the benefits and drawbacks of responding directly? Is there a better means of heading off potential misinformation? If so, what outlets or venues might be useful? Do you even need to respond at all? Consider here the role of the algorithm on social media.

- Who might you reach out to in your community to talk about the purpose of your Pride display? Would you address the misconceptions brought up on social media or not? If so, how?

- How would you inform your staff about the situation? In what ways would you explain the FOIA request to them and what they would need to do?

- What information would you or your institution’s FOIA officer need to provide the reporter from the request? What could you do to protect the identity of individuals in your organization who may not wish to have their identities shared with a reporter (i.e., a trans employee who may have had no connection to the display but who has their pronouns in their signature)?

- Would you reach out to the reporter or the outlet they work for to talk about the Facebook post? What if they were not amenable to sharing the story they’re working on with you? If the reporter were amenable, how would you answer questions they pose if those questions challenge the purpose of a Pride display in the children’s section of the public library?

- How would you ensure you protect you and your staff from similar FOIA requests in the future?

- How or where would you create safeguards to head off potential future situations like this one?

Post-Module Reflection

- Did your thoughts from the premodule questions shift as you moved through the readings, videos, and activities?

- What is one big thing you will take away from this lesson and implement into your work? What is one thing you are eager to share with a friend or colleague?

How was Your Experience?

"*" indicates required fields